Do you document for the sake of documenting?

Questions surrounding quality and quantity in early childhood documentation is not new

After doing training with a number of services one of the questions that is most often asked is "How many observations should we be doing?"..."How do I know I am doing enough?". I believe the fear of not having enough documentation is not a new one. Ever since the National Accreditation System came into place and emphasis on documentation of learning and auditing of this process began educators have questioned themselves as to whether they are doing enough.

Currently there still is no specific guides on what the 'minimum requirement' for documentation and assessment, rather assessment guidance is qualitative and left to individual judgement assessing a wide range of variables such as:

- the type of care;

- use (when and how often each child used care);

- demographic and language factors;

- service philosophy and education methods etc.

As educators there is a fear of failing due to lack of documentation. We are all looking for a book that will tell us if we do this many per child, per week, month, year we will meet the standard. However, minimum requirements for 'early childhood programming', outlining what is passable and not passable is very difficult to articulate with 'one simple catch all rule'. Furthermore in addition to individual service factors , and it cannot be understated, is that not all observations are made equally. Detailed observations often contain significantly more information about a child, whereas quick jottings and anecdotes provide only one or two elements from which a teacher can use to assess and/or extend learning upon.

So my answer of course to the question of 'how much is enough' is normally answered by reframing the question into: 1. 'Are your observations providing you with enough quality/valuable opportunities to follow through or follow up on learning for all aspects of your program?' and 'have you observed enough to communicate to all stakeholders confidence that each child is enjoying and progressing well using your program?'. Answering these questions while also challenging, are more meaningful and I will explore the ideas and issues surrounding these two questions below.

Quality observations should always be meaningful

Quality early childhood education is based on rich (detailed) and meaningful observations that encompass many things. Let's just take a moment to explore what makes up a meaningful and rich observation observation.

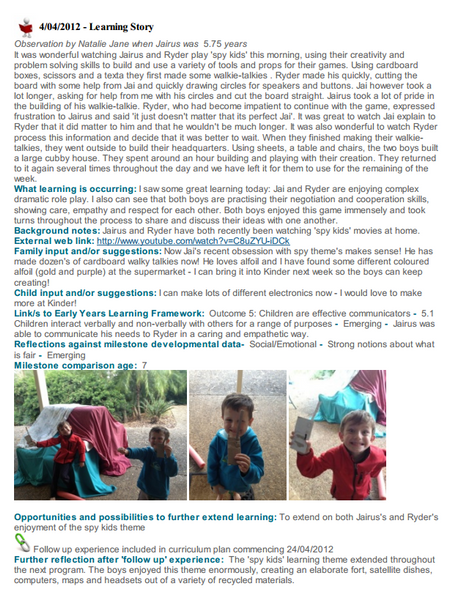

Meaningful? I believe the first thought in your mind when you are taking an observation should be "What is the child learning in this moment?" I am not saying that this always means that it has to be measurable such as; writing their name, taking a first step or using a pincer grip. These are all aspects of learning but as we evolve as educators we realise that many of the learning steps children take are not always able to be seen by the naked eye. We as educators should be looking for and recognising these moments; which is what differentiates us as quality teaching professionals. It requires time, thought and continuous reflection to master and often involves picking up "the little things" often overlooked by the unqualified observer. The observation below will show an example of this.

Sarah you were playing in the home corner today with Jenny and Marie. You all took turns in pouring each other cups of tea and using your manners to say please and thank you to one another. When Barbara called you all to come to the mat you put the tea set down and called out to Jenny and Marie that it was time to come to the mat. This was lovely to see that you are gaining confidence within your friendship group to communicate with them and also your sense of belonging in the larger group that you were happy to shout out this instruction to your friends in front of others.

This observation does not explicitly demonstrate an obvious significant traditional learning milestone, however we as qualified early childhood educators understand its importance and that if a child feels confident and part of the group, they will learn and grow. The observation clearly shows that Sarah is confident and comfortable in the group which is one of the first steps to engaging in the learning environment that is being provided. It also shows that she is an active participant in this program.

Furthermore, the observation can be defined as rich as it also subtlety illustrates many other important pieces of information about Sarah that we can use to create future learning opportunities with. Her enjoyment in role play and small group social interaction, her ability to follow simple instructions, her ability to take on a leadership role when she finds it necessary and her ability to communicate clearly with others. Any of these learning attributes are able to be readily built upon and/or extended. I will explore this further below.

An example of an observation, while still valid but far less rich, which misses many opportunities to observe and/or follow up on learning:

Milly picked up the paint brush with a palmer grip and did three big brush strokes

This observation does not show whether Milly enjoyed painting, how long she was at the activity, whether anyone else interacted with Milly at the time etc. This leaves the reader of the observation wondering why the observation was taken in the first place. Possibly at a stretch you could state the learning taking place was that Milly is able to manipulate a paint brush. When you could have watched Milly for another 2 minutes and documented in a way that was meaningful a plethora of learning may have been discovered.

Quality observations should be written considerate of all stakeholders

Readers of Sarah's observation (above) will get many different things, for example:

- Sarah's parents will see that she is happy when she is attending the service and that she is making friends;

- Colleagues, carers and other educators may be provided with insight or learning about Sarah, they may not yet have observed;

- The child Sarah (with help) will see that her play and progress is being celebrated and acknowledged even when she didn't realise it was occurring, giving her the confidence to continue playing this way;

- Regulators will be able to see that the program is engaging children with and that the educator knows the child and is following up on opportunities observed.

When taking an observation you should be aware of what you are communicating to the people that are reading it and that the message that you are sending is the one you a meaning to send.

Follow through is vital - quality observations should always provide the foundation for future learning opportunity

In saying all of this the above observation means significantly less if you as the educator don't follow through. Yes parents may feel comforted seeing evidence of the child involvement, but if it is not followed through with assessment of learning and/or a programmed activity, the observation does not meet the needs of other stakeholders yourself, your service and the regulatory authorities.

This is where the true beauty of effective programming comes into play. A well written observation should lead to either confirmation that your existing teaching program is meeting the child's need and/or an assessment that leads to a new a programmed activity. The observation process should then cycle again: to review whether or not this programmed activity worked as you expected it to you need to observe the child engaging with the activity, you then take an observation of this engagement which leads to another programmed activity and so on and so forth so that before you know it the programming cycle is practically doing itself. All from your original observation you have now created a rich tapestry of a child's learning.

Summary

In summary the question of quantity should not be the focus, rather educators should take time to step back and really reflect on whether they can answer the following questions for each child in their care:

- Do my observations communicate the important things I have learnt about that child, providing opportunities to collaborate with families and colleagues;

- Do my observations show the child's engagement/enjoyment of my program?; and

- Have I followed up on what I have observed to further engage and/or extend learning for that child.

If quantity really still concerns you, step back again and look at your programs. Can you say that the majority of your practice and experiences offered are always guided or initiated by the children you are observing?

Being an educational leader in an early childhood service is a hugely challenging role, particularly in light of changes to curriculum that have occurred over the last two years with implementation of the new National Quality Standard and the Early Years Learning Framework.

Being an educational leader in an early childhood service is a hugely challenging role, particularly in light of changes to curriculum that have occurred over the last two years with implementation of the new National Quality Standard and the Early Years Learning Framework.

Turning Differences into Opportunities

Turning Differences into Opportunities