Demonstrating Responsive Programming Using LIFT

Important Preface:

A brief note about 'cycles'Before showing you how to link your observations to planned learning experiences in LIFT, we first need to explain how LIFT sorts and records learning experiences into 'cycles'. In LIFT, we use the term 'cycles' as the majority of teachers plan cyclically: daily, weekly or monthly. However, it is important to note that we also understand that flexibility is paramount, therefore in LIFT you do not need to stick to any particular programming cycle and can vary the start and finish date of any 'cycle' to suit your individual teaching needs and curriculum. If you do not plan cyclically, it is probably more helpful for you to think of a cycle in LIFT as a grouping date against which you will record a number of experiences. It is probably also helpful to note at this point that LIFT also allows further flexibility for you to only run certain experiences on certain days within a planning cycle. These can be recorded against the day provided and/or in the instructions and notes of the experience.

Understanding the meaning of being 'responsive'Too often teachers confuse the requirement of providing a 'responsive curriculum' with 'emergent on the day' planning. There is nothing wrong with 'planning in the now' provided it is implemented well, however equally there is nothing wrong (or less responsive) with planning follow up experiences next week or even next month. We believe that teachers should focus more strongly on being timely. That is, teachers need to respond to children's learning cues/needs and follow them up in such a way that is:

- still effective (the original objective is still valid and the follow up learning is still meaningful); and

- is practical and allows teachers sufficient time to plan and prepare resources and activities that support that learning.

More often that not a timely 'follow up' will be to 'follow up' the learning immediately or in the next program. However, there are times when a timely response might be linking a current observation to a future cycle weeks if not months in advance. Here are some great examples of reasons why a teacher may wish to program weeks or even months in advance:

- it's winter (football season) and a father tells you that his son loves watching the one day cricket matches with him. A great immediate response to this might be to put cricket on the current program but what about linking this up to the cycle in summer that corresponds with the first one day cricket match. How amazing would it be to prompt sharing of this activity at this time.

- it's currently March and a child who recently immigrated from India has just joined your centre. You discuss with the child's family cultural issues. The child's mother tells you that the child loves to make friendship bracelets from the 'Friendship Festival' celebrated in India in August each year. Yes you could put friendship bracelets on the next program but creating a whole follow up experience in August would also be very special to both the child and their family.

Retrospective documentationWhile LIFT supports 'forward planning', there will be many times where you will observe and respond to children's learning with experiences on the spot. In such circumstances you will be entering your planned experiences after you have already ran them. While this always is challenging for teachers to keep their documentation as current as is practicable, this practice is not discouraged and we advise that teachers use complementary methods, such as brief hand written notes on their plans, to communicate modifications to their daily learning offerings. Later you can use LIFT to describe in more detail reasons and reflections for changes and additions to your programs.

Auditing & ReviewLIFT allows educators to audit and review their work using a number of tools. One tool is our observation auditing tool which counts the number of observations and how many were linked/followed up by a 'follow up' planned experience. There are no hard and fast rules for how often this should be done, but as a general rule there should be evidence that it occurs regularly for all children. An example of this might be to see at least half of the observations over the last 3 months have been followed up with planned experiences.

Planning an experience following an observation

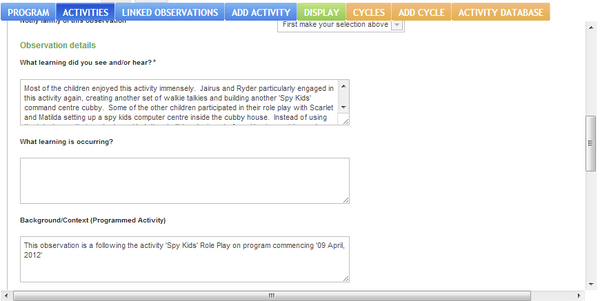

Step one: When entering your observation....

In the "Future Opportunities and Possibilities" make a quick note about an experience and if required and objective that you want to achieve. Select the cycle you wish to follow up in. You don't need to note this elsewhere to remind you to follow up this, these are automatically listed/ 'ready to use' when you open the cycle you have link to.

Step two: Use prompts from step one ("Linked Observations") to guide your planned experiences.

After opening your program cycle. Click on the "Linked Observations' tab. This will show all the observations and any prompts/objectives you noted that you wanted to follow up in your program. We recommend that you review all the observations carefully first as it may be helpful for you to combine the needs of more than one child with the one experience.

For example:

You wanted to do more "counting" activities for Mark, another dramatic role play activity for Sarah and do some more writing experiences with Tabitha. A great follow up experience for all these children might be a shop play area where you could offer:

- writing of signs, orders and receipts

- labeling of pretend sales items

- pretend money

- dress ups and props such as aprons, baskets etc.

Step three: SHOWING LINKS BETWEEN EXPERIENCES & OBSERVATIONS

LIFT is designed to be flexible. We believe strongly that documentation should support the demonstration of linkage however also not to be too onerous on the teacher. Sometimes teachers may wish to explicitly link a child/child's observation to an experience, other times you may wish to provide a general note. Here are two ways you can show linkage in LIFT.

1. Add an activity that directly correlates to a prompt/objective.

For example in your 'future opportunities and possibilities' your write: Provide a sand experience for Paul to extend on Paul's current enjoyment of this activity. If you were then to provide a Sand experience, no detailed explanation is required. Another teacher or a validator can readily see the correlation.

It is important to note that the connection should be obvious, hence had the teacher written "provide a sensory/construction experience for Paul" then it might be a stretch for another person to be able to readily make the connection/link to a 'sand play experience' and we would recommend using the methods described below.

2. Add an activity and link to a observation/child or multiple observation/children

LIFT prompts you to describe why you linked to an activity ("Reasons for this experience"). When creating activities you can choose to manual describe your links or to use the drop down menus to link to one or more observations/children.

Before doing this it is important to note that linking to observations/children in LIFT takes time. Normal LIFT forms take 4-5 seconds to load, however when linking to observations it takes approximately 20 seconds for each linked observation. It is for this reason we recommend that you take a moment to think about how you wish to write up your 'reasons' to save any unnecessary wait time.

1. Add activity with 'No linked observation' - use this as the fastest and quickest way to add an activity without linking an ob (4-5 second load time). Write up links in the notes under "Reasons for this experience".

2. Linking to one observation: Add activity with with a linked observation (20 second load time)

3. Linking to more than one observation: Add activity as per point 1 and then "View and Edit" the observation to add multiple

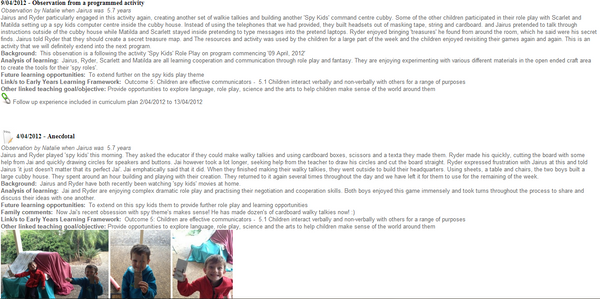

Step four: Evaluating a follow up experience

Sometimes we are prompted to provide a learning experience without individual learning objectives and hence in such circumstances a follow up to an individual observation is probably not required. In this way, our general reflections provide sufficient opportunity to reflect on how an experience went.